Objective: Abdominal dyskinesia, often referenced as belly dancer syndrome, is a poorly understood clinical presentation involving involuntary, undulating movements of the abdomen.1 Few cases have been reported, though one of particular interest in our patient study involves a case of parkinsonism with abdominal dyskinesia in the presence of schizophrenia.2

Background: A 69 year old male with a history of impaired cardiovascular system, anxiety, and depression presented to the movement disorders clinic reporting a one-year progression of abdominal spasm. His symptoms were described as constant unless positioning in prone, holding his breath, or taking hydrocodone-acetaminophen. Upper abdomen exhibited intermittent sinuous movements, not clearly distractible but partially suppressible. He was treated with clonazepam, lorazepam and gabapentin. He then returned in two months and exhibited no abdominal movement until addressed by neurologist, though the movement quickly resolved. EMG study, MRI, comprehensive metabolic panel, B12, and T4 were normal. The patient returned after one year. At this follow-up visit he was agreeable to pursuing physical therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical examination was unremarkable.

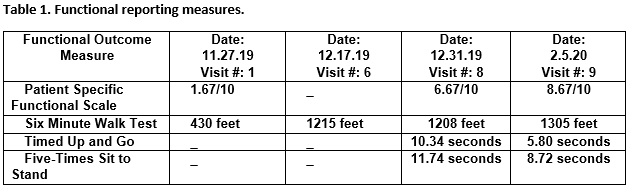

Method: He presented for physical therapy (PT) evaluation within two weeks and exhibited bradykinetic gait, decreased arm swing, and postural tremor of the left index finger. Complaints of spasm were distractible and bradykinetic gait was largely corrected following verbal cues.

Results: The patient demonstrated an exceptional response to verbal encouragement and education regarding neuroplasticity. Measures of walking performance significantly improved during his initial month of twice-weekly visits. A one month hold was used to encourage self-efficacy and retention via independent home exercises. He returned after hold to demonstrate further improvements on all physical measures. Complaints of spasm were minimal and patient engaged with motivated, thoughtful demeanor. He reports return to prior level of function.

Conclusion: Abdominal dyskinesia is poorly understood and it is necessary to rule out additional pathology while initiating interdisciplinary treatment. There is currently no evidence-based treatment recommendation.3 However, a positive response to treatment strategies recommended for the management of functional movement disorder (FMD) was achieved in this patient case.

References: 1. Iliceto G, Thompson PD, Day BL, Rothwell JC, Lees AJ, Marsden CD. Diaphragmatic flutter, the moving umbilicus syndrome, and “belly dancer’s” dyskinesia. Mov Disord. 1990;5(1):15-22. doi:10.1002/mds.870050105 2. Vasconcellos LF, Nassif D, Spitz M. Parkinsonism and Belly Dancer Syndrome in a Patient with Schizophrenia. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2019;9:1-2. doi:10.7916/tohm.v0.654 3. Yeh JY, Tu KY, Tseng PT, Lee Y, Lin PY. Acute Onset of Abdominal Muscle Dyskinesia (“Belly Dancer Syndrome”) from Quetiapine Exposure: A Case Report. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2018;41(2):73-74. doi:10.1097/WNF.0000000000000271

To cite this abstract in AMA style:

R. Hand, J. Snider, J. Utt. Managing Functional Movement Disorder in Outpatient Physical Therapy: A Case Report of Belly-Dancer Dyskinesia [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2020; 35 (suppl 1). https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/managing-functional-movement-disorder-in-outpatient-physical-therapy-a-case-report-of-belly-dancer-dyskinesia/. Accessed October 17, 2025.« Back to MDS Virtual Congress 2020

MDS Abstracts - https://www.mdsabstracts.org/abstract/managing-functional-movement-disorder-in-outpatient-physical-therapy-a-case-report-of-belly-dancer-dyskinesia/